Altyre to Edinkillie – The First Encounter

Andrea Turner is a multi-disciplinary artist living in Forres. Her work spans visual art, music and poetry, and she is currently working with Combine to Create. In Altyre to Edinkillie –The First Encounter, Andrea explores the very beginning of her residency.

When I first found out that my Small Halls Artist Residency was to be at Edinkillie Hall I knew I had to go on a journey – one which would enable me to physically feel the story of the land and then locate the historic hall, not only near the centre of Edinkillie parish, but also at the heart of my awareness.

My most recent creative work is a year-long conversation with a rewilded garden on the Altyre Estate, a poetic work I’ve titled Small Wood. It makes sense to start from here: I turn from the arch in the garden wall that leads to Small Wood and step away, through the farm and up the track to Squirrelneuk Bridge, passing under Scurrypool bridge and down to Scurry Pools where I connect with the Dava Way. My creative practice over the past five years has drawn me deeper into the natural pace and rhythms of my body. Moving at body-speed allows and invites me to be in relationship with the landscape, with the animals, trees, rivers, sky and stone. I am walking through the land as generations have done before, feeling my feet in their footprints. Slowing down enables expansion – I sense the world more intimately, create many rooms inside myself for life to reside. In truth, though, I have always been slow – perhaps more carthorse than steed.

The sky is renaissance blue, a lapis dome lit with birdsong. It’s hot. Flies buzz round me, attracted by the salt and sugar of my sweat. The dry ground gripes and cackles under my bicycle wheels. The path from Clashdu at the Edinkillie Parish boundary is hard-packed, stony, covered in clover and grass, flanked by purple rhododendrons, young oaks and aspens pale with moss. Since childhood I have gathered images, and when filled with nature’s painting I feel unbound. We do not deny the world’s suffering by loving its splendour. These days I say to my adult children, “it’s okay to be happy,” battered as they are by stories of our own destruction. “It’s okay to be happy, then maybe you can help.”

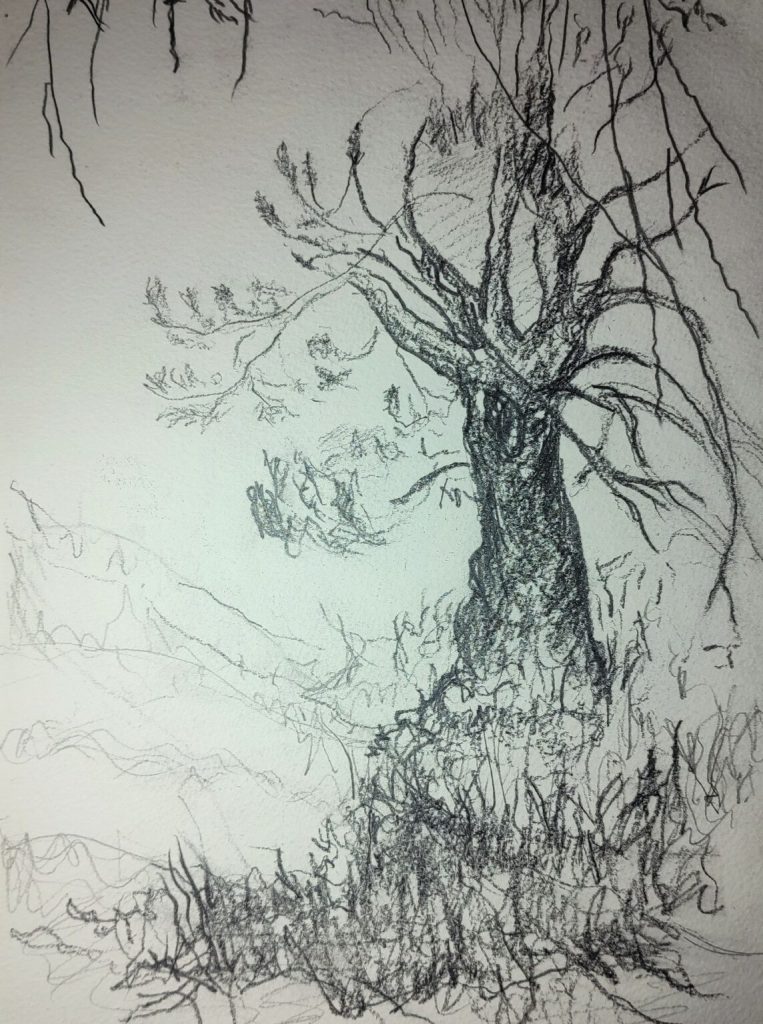

I pass a small area of burnt gorse and feel the day’s unusual heat burrowing into my bones. Memories of an unwise solitary walk through the bush near Tafi Atome in Ghana scorch my senses: I smelt smoke then heard the crackle of flames in the flint-dry undergrowth and, genuinely scared, I began to run faster and faster, heart pounding, until I heard a motorbike and from clouds of dust a young man appeared. We sped away, the bike lurching under my weight, across deeply rutted, smouldering earth. Here, in north east Scotland, looking at the blackened gorse, I recall our wildfire in 2019 that raged for four days across over 20 square miles of moorland, destroying around 350,000 trees. Meadow pipits, hen harriers and merlins lost their nests and eggs. Mountain hares, grouse, pine martins, skylarks, curlews, adders – all displaced. One thousand acres of native pinewood, planted to aid the regeneration of the Caledonian Forest, gone. For weeks afterwards smoke was visible rising from these hills. A small tree casts a perfect shadow across the path. I stop to take a photograph. The tree and its shadow attract first my eye, then my mind. I want to know this tree more deeply. I lean my bike against the verge and, taking a sketchbook and pencils from the pannier, begin to draw.

After miles walking in this ‘Dreamtime’ I reach Edinkillie Hall. All the windows are frosted – there is no view in, nor presumably out. The building is locked, deserted. Behind the hall struts a large pylon with a hissing, popping metal box attached and, to the front, there is the busy main road. I sit writing a first draft of this blog in the ‘Breathing Space’ near the old Dunphail railway station. There’s a marked contrast between the sounds of the hall environment and the sonic landscape of the wind, birdsong, sheep and distant tractors of the Dava Way. I’m not yet sure how to best serve the hall and the people who live locally nor how to creatively witness this landscape. Next time I come I will meet a key holder, go inside Edinkillie Hall and the conversation will begin.

Nearby, builders are renovating the railway workers cottages. A dog barks, the builders roar at it to be quiet. From their radio a singer pleads: I Want Your Love, I Need Your Love.

Three weeks later and I’m back at Clashdu at the start of another walk, this time to the far boundary of Edinkillie Parish on the Dava Moor. A creamy mass of elder flowers leans over the gate, I pass through bathing in their delicate scent. The stubbled path is softened by thick green shoots after days of rain. Wind turbines pant, an infrequent ‘bang’ fails to scare the crows. It feels good to be here among the singing breeze. Landmarks on the route greet me – here’s the stone bridge standing high over an overgrown track, its unwalled edges beckoning. Here’s my tree with its perfect shadow. And here is Edinkillie Hall opening its doors to me. I’ve been inside the hall, met some lovely people – we’ve sung together, written poetry, made art. New relationships have begun, conversations shared. And I am the one who gets to linger, listening to the echoes in her wooden walls when today’s visitors have gone.

This blog post was originally published on The Findhorn Bay Arts website on 28 August 2022 and we share it here with permission from the author.